Historian Dr Jason Price sheds light on a neglected artist and one of The London Group’s founding members.

Next month marks the 140th birthday of London Group founding member Thérèse Lessore (1884-1945). Although she was a prolific champion of The London Group, showing 107 paintings with the group across her lifetime, the artist tends to be remembered now as the third wife of another London Group founding member, Walter Sickert, rather than an artist of distinction in her own right — a fate all too common for professional female artists from this period. This overshadowing has been compounded by a lack of scholarly and curatorial attention both during and beyond her lifetime, something which, through my own research, I am hoping to begin to rectify.

Born on 5 July 1884 in Steyning, West Sussex, Elaine Thérèse Lessore was the youngest of three children belonging to Jules and Ada Louise Lessore. Jules was a well-known marine painter who sometimes dabbled in pottery, while census records indicate that Ada Louise was at one time a sculptor. The combined artistic parentage seems to have had an impact on the children since all three entered creative professions in adulthood. For Thérèse, this was painting. Her passion for art apparently bordered on an obsession, with close friends later recalling it as a topic she could speak endlessly about. Between 1904 and 1909, she studied at the Slade School of Art, winning the prestigious Melville Nettleship Prize for figure composition in her final year. Soon after, she married painter and textile designer Bernard Adeney and together, in 1913, they would be two of the founder members of The London Group. For the group’s first exhibition held at London’s Goupil Gallery in March 1914, the art critic for the Daily Herald hailed Lessore’s work as being ‘really original’ and possessing lasting appeal. Later that year when some of her paintings were exhibited at the Whitechapel Gallery, Sickert singled her out for distinction in his review, describing her work as ‘some strange alchemy of genius’ of the ‘highest technical brevity and beauty’. For Sickert, what made Lessore’s work distinctive was a refusal of precise or detailed realism in favour of capturing something of the essences within the subjects she chose to paint. The two artists would develop a close friendship, and, in the summer of 1926, they were married (Lessore’s marriage to Adeney had ended in divorce in 1921). 24 years her senior, Sickert’s health was already on the decline when they married, but they would nonetheless enjoy 14 years of marriage before his death in 1942. As Mrs. Sickert, Lessore was a companion, carer, and artist’s assistant – sometimes squaring up and completing Sickert’s paintings. Letters to personal friends during the period of their marriage reveal that while her admiration for Sickert was unwavering, these years were challenging – and it is notable that her personal contributions to The London Group’s annual exhibitions during the corresponding timeframe dwindled.

Although she dabbled in porcelain painting, Lessore was primarily a painter, typically working in oil and watercolours. Across her oeuvre, one will find scenes of various sorts: moments of domestic familiarity, bustling street scenes, Kent hop pickers at work, and the circus (and much else). As a theatre historian, it is her circus works which I have been particularly drawn to. Although the modern circus dates to the eighteenth century, it came into its own as commercial entertainment in the nineteenth century and was regarded by some artists at that time as a visual metaphor of the industrialising modern world. It was innovative, spectacular, and colourful, showcasing bodies in many forms, often in costumes which gave no illusion to what might rest underneath (it was subsequently erotic as well). To depict mass entertainment of this kind, regarded as low culture, in fine art was a daring and radical choice – and one which came to define some of the modern art movements and pioneering artists of this period who rejected traditions and subjects of the past, adhering to poet and critic Charles Baudelaire’s assessment, set out in his 1863 essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, that to rely on the techniques and subjects of the past to record the present was likely to produce a world that was ‘false, ambiguous and obscure’. This radical trend first emerged in France in paintings by, for instance, Edgar Degas and Georges Seurat, but soon spread across Europe. Sickert began painting the occasional circus scene in the mid-1880s (alongside music hall) and by the turn of the twentieth century such topics were more commonly treated by other British moderns as well.

Astute readers will already have identified one of the common denominators across the artists mentioned above: they are male. While this, in part, reflects the wider patriarchal social system at the time, and indeed of the artistic profession as well, it is notable that the topics deemed appropriate for women artists to paint were much more restricted than they were for men, often consisting of environments and spaces in which they were regarded as specialists, such as the interiors of homes. Although the range of ‘acceptable’ topics expanded alongside professional opportunities in the twentieth century, women like Lessore, in selecting to paint circus scenes, were taking on a field historically and artistically regarded as the domain of the male artist.

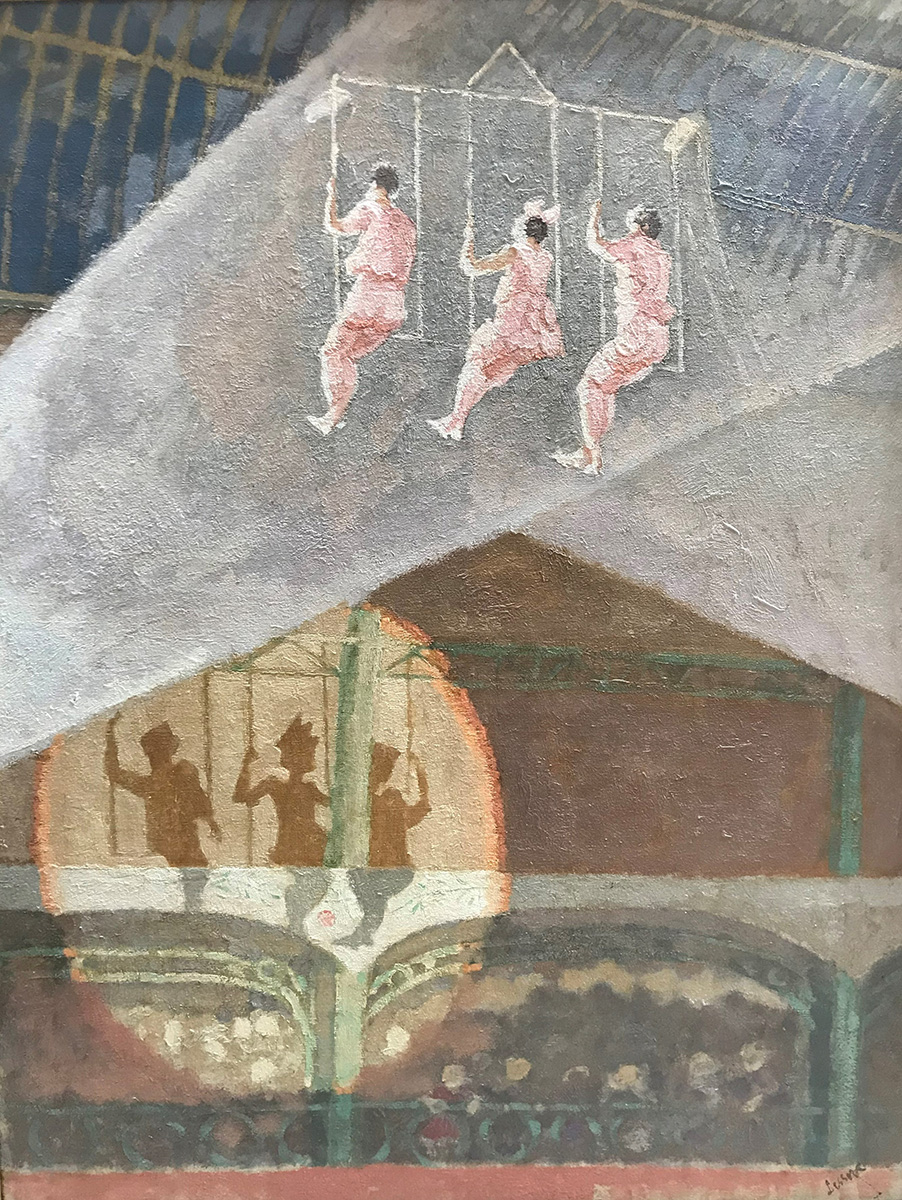

Although she is known to have painted several circuses across her career, it was the annual Christmas Circus at the Royal Agricultural Hall (today known as the Business Design Centre) in Islington that constitutes the largest portion of her circus works. The circus at the Royal Agricultural Hall was a regular Christmas event in Islington, with the earliest circuses being staged there just a year after the building was completed in 1862. From 1920 to 1938, the fair’s circus was overseen by John Swallow, a skilled equestrian who had secured his reputation in the circus industry with his famous Broncho Bill Circus and Wild West Show which toured Britain in the 1910s and 1920s. Although there’s evidence to suggest that Lessore began an interest in the fair as early as 1918, it was Swallow’s Circus that held her attention, particularly between the years 1927 and 1934 when she and Sickert were living nearby. In my recent book, The Art of Entertainment: Popular Performance in Modern British Art 1880 – 1940, I look specifically at these paintings and work to contextualise both Lessore’s and Swallow’s work, arguing the significance of both in British culture at the time. In my reading of Lessore’s paintings, they not only record a major early twentieth century circus of distinction (in which few other visual records exist), but they also demonstrate the remarkable skill of an artist who can so capably record the vibrancy and energy of the circus environment. One of the few other female artists to do so in Britain at this time is, of course, Laura Knight, whose more precise, realistic style offers an equally useful, albeit very different, visual record of circuses in this period of history.

For those who take the time to hunt out her works, it soon becomes clear that Lessore deserves more respect than she has been paid – she was a modern artist of distinction, sometimes working in radical ways with the subjects she chose to paint. Readers keen to learn more about Lessore’s work are in luck as there are several upcoming opportunities to do so. Her painting The Daredevils (Figure 2), made in 1929-30 of Swallow’s Circus, is currently exhibited as part of the Discovering Degas and Miss La La show at the National Gallery, which runs through 6 September. Within the context of this exhibition, I will be delivering a talk about Lessore on the date of her 140th birthday (5 July). Links to reserve free tickets to the talk can be found here. Another upcoming event is Thérèse Lessore and the Circus, which will take place at Islington Museum, on 8 July from 2.30 to 4.30pm. This is an artist’s open house showcasing some of Lessore’s circus paintings, including Miss Lulu and Mr Harry (Figure 1) and Swallow’s Liberty Horses (Figure 3), which feature in this piece.

Jason Price, 2024

Jason’s book, The Art of Entertainment: Popular Performance in Modern British Art 1880-1940, published by Routledge, is available now.

Dr Jason Price is a theatre historian and Reader in Theatre & Performance Studies at the University of Sussex. His research is concerned with the relationships and intersections between performance, politics and popular entertainment since the Industrial Revolution. He is the author of ‘Modern Popular Theatre’ and ‘The Art of Entertainment: Popular Performance in Modern British Art 1880-1940’. His third book, ‘Researching Popular Entertainment’, co-edited with Dr Kim Baston, will be out later this year.