Continuing our series of historical female artists linked to The London Group. Art historian Brigid Peppin reflects on the roller coaster reputation of Helen Saunders.

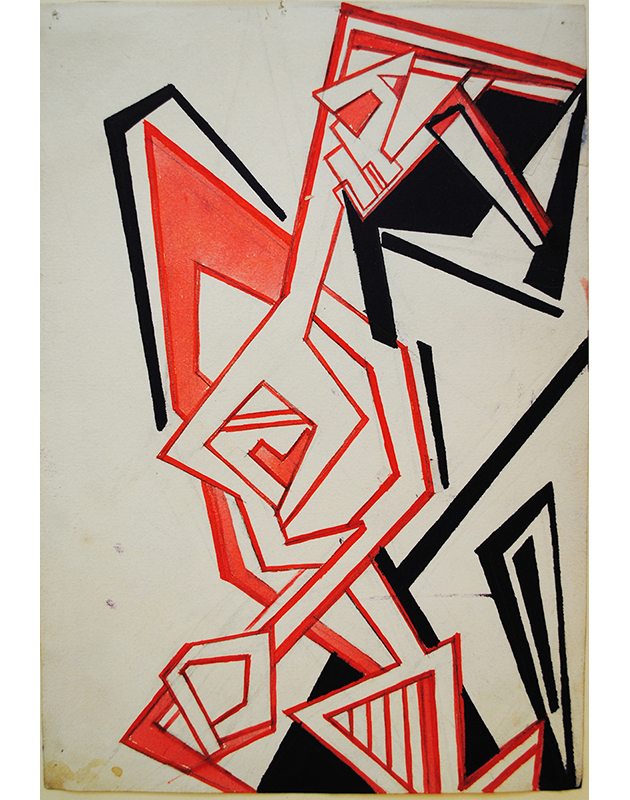

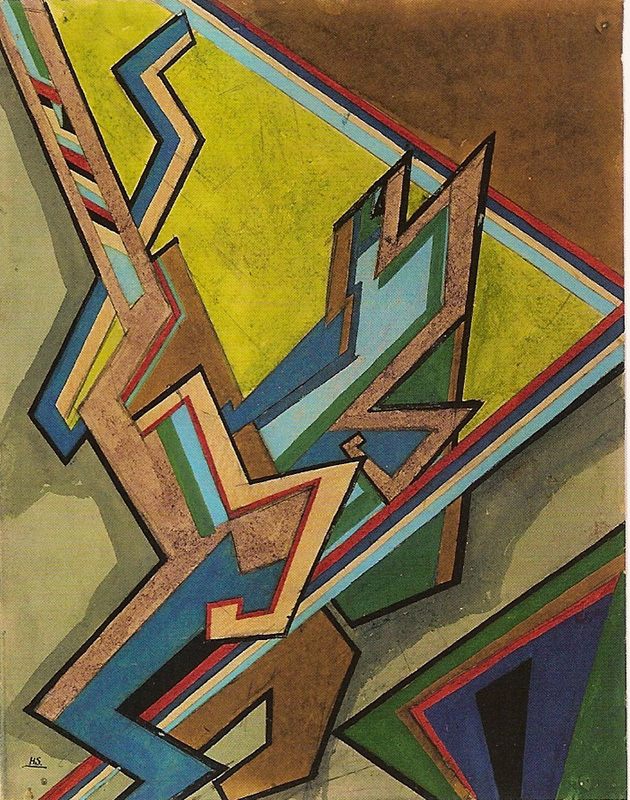

If the Vorticist painter Helen Saunders (1885-1963), who is represented in the exhibition ‘Now You See Us’ at Tate Britain, had been able to foresee the posthumous interest in her work, she might have been surprised, since between 1917 and her death in 1963, only three of her paintings appear to have been exhibited in professional venues.1 Her career had started with considerable acclaim; her post-Impressionist paintings were selected by Roger Fry for his ‘Quelques Independents Anglais’ at the Galerie Barbazanges, Paris (1912) and Grafton Group (1913); she showed at the Friday Club (1912), at the Allied Artists’ Association (1913) and had two works selected for the ‘Twentieth Century Art’ exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery (1914). She contributed radically abstract works to the Vorticist exhibitions in London (1915) and New York (1917) and exhibited two paintings with The London Group in 1916. But from then on it seems that she showed virtually nothing – a still life in each of the 1930 and 1931 London Group exhibitions and a painting with the A.I.A. in 1940. Though she never stopped working, it appears that she largely confined herself to local art exhibitions in Holborn. The contrast between her early successes and her later obscurity is striking, and research into her work and career continues.

The historiography of Vorticism certainly played a part in her reputational roller-coaster. Wyndham Lewis’s egotistical claim in 1956 that “Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did, and said, at a certain period” 2 did the movement and its participants no favours. By then a Bloomsbury-centred narrative had prevailed for decades, initially prompted by the Ideal Home rumpus of 1913 when Lewis, after seceding from Roger Fry’s Omega Workshop, gratuitously antagonised the group by sending an abusive letter to its patrons. Clive Bell’s 1917 dismissal of Vorticism as “a puddle of provincialism” 3 typified early 20th century art historiography, and it was not until Richard Cork’s seminal exhibition and two-volume study in the mid-1970s 4 that Vorticism began to gain a presence in the art historical canon.

Saunders committed herself wholeheartedly to Vorticism; she signed its manifesto (albeit with her surname intentionally mis-spelt), contributed drawings and a poem to ‘BLAST 2’ and took charge of its distribution, helped to run the short-lived Rebel Art Centre, participated in the Vorticist exhibitions in London and New York, collaborated with Lewis on murals and panels for the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel in Percy Street and typed Lewis’s articles and novel Tarr when he was in the army during WW1. Lewis had already insisted that she read a notoriously misogynistic work, Otto Weininger’s ‘Sex and Character’ which, chiming with the prevailing prejudices of the period, asserted the intellectual and creative inferiority of women. Although a close study of their respective Vorticist works shows that in terms of visual ideas Lewis probably learned at least as much from Saunders as she did from him; the letters from her that Lewis chose to preserve seem to indicate that, perhaps to bolster his own self-esteem, he systematically undermined her self-confidence.

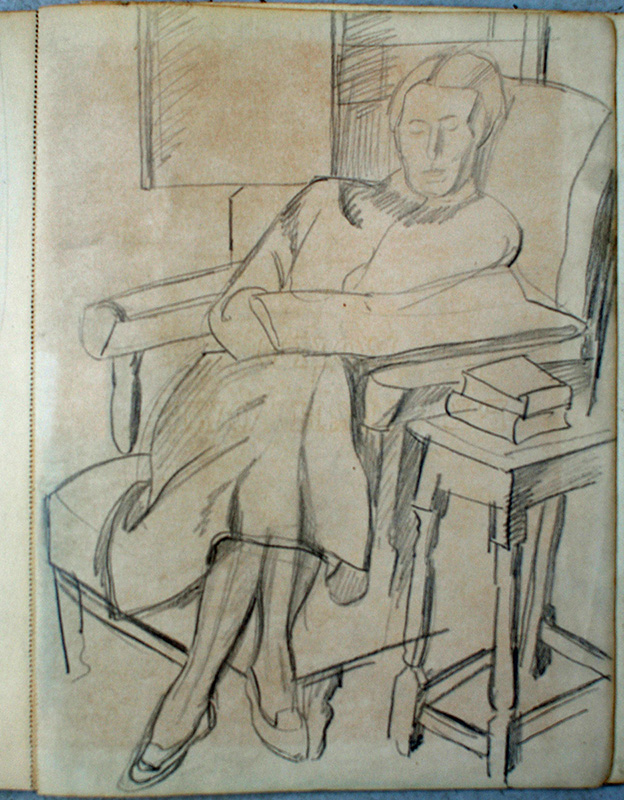

Artworks by artists without a ‘name’ are particularly vulnerable to deliberate destruction and accidental loss. Saunders herself could only find one Vorticist drawing when asked to contribute to the Tate’s 1956 exhibition ‘Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism’.5 It was not until after her death in 1963 that a cache of Vorticist and other works on paper was found in her studio at the bottom of a heavy oak chest. In 2009 three further Vorticist watercolours, exhibited at the Penguin Club in New York in January 1917 and presumed lost, were rediscovered, uncatalogued, in the collection of a private college in Chicago. Other examples have proved impossible to recover. One of her Vorticist oils, used by her sister in the late 1950s to cover her larder floor, was subsequently burned because it had become mouldy.6 The four works 7 that she showed with The London Group in 1916, 1930 and 1931 have disappeared, and many paintings are thought to have been lost when her flat in John St, Holborn, was badly damaged during the Blitz. In all, only about 200 works by her are currently known from a working career of some sixty years. Her two surviving sketchbooks, along with letters, other documents and several oil sketches, have now been placed in the Tate Archive, so they at least will be preserved for posterity.

The most striking rediscovery of anything by Saunders took place in 2019, when Courtauld postgraduate researchers Becky Chipkin and Helen Kohn found, through X-rays, that her large, ambitious canvas ‘Atlantic City’ (1914-15), which disappeared after the 1915 Vorticist exhibition, had been overpainted by Lewis and remains hidden underneath his portrait ‘Praxitella’ (1921-22, Leeds Art Gallery).8 Lewis had broken off his long friendship with Saunders in 1919, and she then experienced a serious breakdown. His re-use of Saunders’s canvas occurred at a rare moment when he was relatively well-off, having recently sold a house in Stockport inherited from his father,9 so it would seem that his obliteration of what was probably one of Saunders’s largest and most ambitious Vorticist paintings was not due to financial necessity but represented a ‘wiping out’ both of their longstanding relationship and of her most conspicuous contribution to Vorticism.10

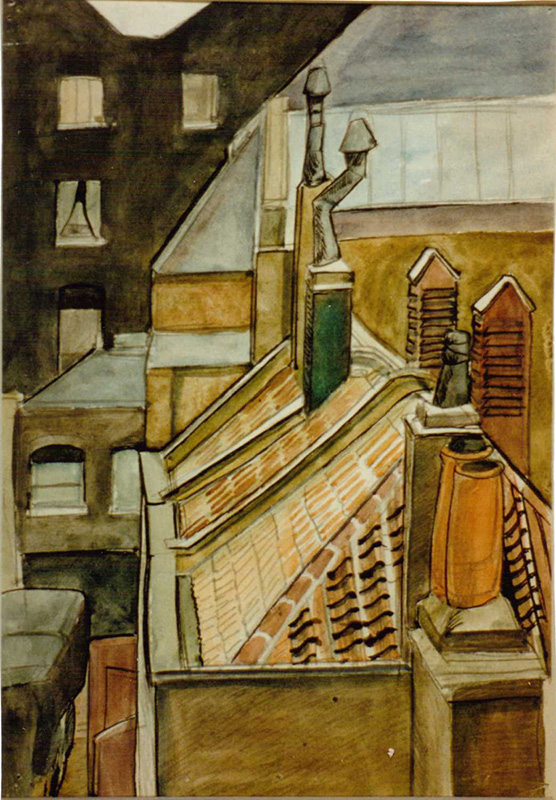

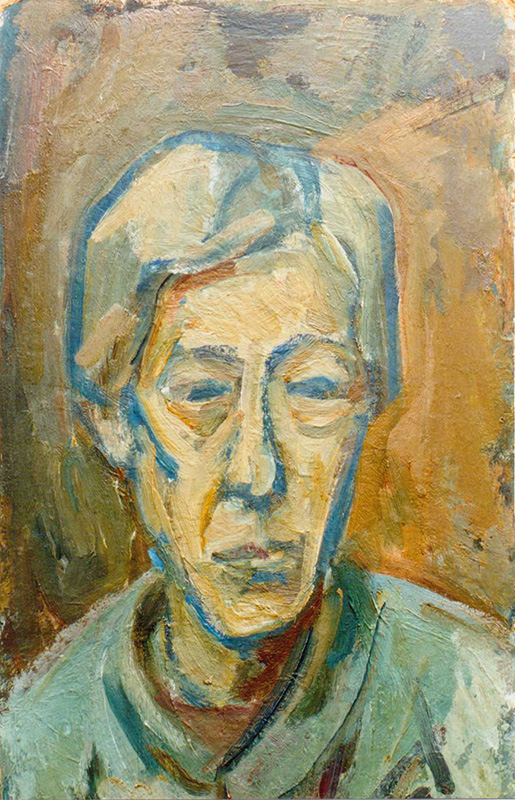

In 1914, Saunders wrote in a letter to Lewis “I shall certainly die if I can’t manage to be some sort of artist”, and she never stopped painting.11 But after her breakdown she withdrew from the competitive professional art world. Her modest private income (from shares settled on her after the death of her grandfather in 1911) meant that she was not reliant on sales and could focus on creative process rather than artistic product. Many of her surviving works comprise landscapes, portraits and still lives and date from the three decades after WW1; a family member who often visited her during the 1930s recalled seeing portraits and “paintings of fruit and they would be gently rotting in bowls as she hadn’t finished the paintings”.12 While her artistic ‘handwriting’ is clearly recognisable across these genres, she did not develop a ‘signature style’ that might have made her paintings more marketable. Instead, she continued to experiment, exploring different ways of applying paint and varied compositional approaches. Though not ‘cutting-edge’, these works demonstrate her continuing commitment to visual enquiry.

It is not known if Saunders continued to submit works to The London Group after her Still Life Group (currently unidentified) was shown in the 1931 exhibition.13 Shortly before her death, replying to a letter from her former tutor and long-term friend Rosa Waugh Hobhouse, she wrote “…I find myself unclear as to what you mean exactly by the grievous encounters (I) must often have had with discouragement. The only place where that seems to be appropriate is that I am ‘discouraged’ when I send pictures to Shows and they are rejected. But I have guarded against that ‘cold water’ for several years now by only sending to the two annual shows in Holborn – and these have always taken 2 or 3 and sometimes 4 (the limit) of the works I have sent them. Then again I am sometimes discouraged and sometimes slightly encouraged by the sight of my paintings hanging amongst the others, some few of which are usually really ‘good’ as I see it.” 14

It seems that Saunders did not recognise how good an artist she still was. Her surviving works from the Vorticist period are all now in public collections, and a catalogue raisonné is in progress. It is to be hoped that a means will be found in future for the relatively quiet and introspective works of her later years to be seen and enjoyed.

Biddy Peppin 2024

biddypeppin.crevado.com

Two works by Helen Saunders are on display in

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520 – 1920

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

16 May – 13 October 2024

Footnotes

1. Saunders has been the subject of two solo exhibitions; ‘Helen Saunders, Modernist Rebel’ (Courtauld 2022) and ‘Helen Saunders 1885-1963’ (Ashmolean Museum 1996). Vorticist and other early paintings by have been shown in a number of other exhibitions including ‘Elles font ’Abstraction’ (Georges Pompidou Centre, 2022); ‘Radical Women, Jessica Dismorr and her Contemporaries’ (Pallant House, 2019-20); ‘Max Weber: An American Cubist in Paris & London’ (Ben Uri Gall, 2015); ‘New Rhythms, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’ (Kettles Yard 2015); ‘The Vorticists’ (Tate Britain 2011); ‘Blasting the Future’ (Estorick Coll. 2004); ‘Modern Art in Britain 1910-1914’ (Barbican 1997); ‘Blast’ (Sprengel Museum Hanover, 1996); ‘Vorticism and its Allies’ (Hayward Gallery 1974).

2. Wyndham Lewis, ‘Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism exhibition’ catalogue introduction, Tate Gallery 6 July-19 August 1956, Toronto and Manchester 1972, p. 142.

3. Clive Bell in The Burlington Magazine, July 1917, pp. 229-30, quoted in William C. Wees, Vorticism and the English AvantGarde, Manchester and Toronto, 1972,p. 142.

4. ‘Vorticism and its Allies’, Hayward Gallery London, 1974; Richard Cork, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age, London 1976.

5. She had hoped to exhibit a small Vorticist oil but was unable to find it. (Letter to Martin Butlin, May 9th 1956 (Tate Archive).

6. Interviews with Helen Peppin, 1995.

7. ‘Painting’, and ‘Waterloo Bridge’, exhibited in 1916; ‘Still Life’, exhibited in 1930; and ‘Still Life Group’ exhibited in 1931.

8. Becky Chipkin and Helen Kohn, Unveiling the Secrets of Praxitella – Lewis, Saunders and the Rediscovery of Atlantic City (unpublished research paper 2023). Read more

9. Paul O’Keeffe, Some Sort of Genius, 2000, pp. 210-211.

10. Lewis made something of a habit of attacking friends who helped him. His secession from Omega was an early example; in the 1920s he ended his friendship with his former Vorticist colleague Edward Wadsworth who had set up a fund to provide him with financial support, and two years afterwards he wrote an exceptionally abusive letter to his former Vorticist colleague Jessica Dismorr.

11. During the war years she seems to have been unproductive; she was unable to paint during WWI when she worked in a government office and acted as an unpaid secretary to Lewis, and in WW2 she worked for the L.C.C.

12. Letter from Julie Littlewood, to Brigid Peppin, 10th March 1995 (Tate Archive).

13. Helen Peppin, a younger relative of Saunders, recalled visiting the London Group exhibition in 1930 or 1930, in order to see her work there. She recalled that Saunders’s oil still life was ‘pale’; like so many of her paintings it now seems to be lost.

14. Helen Saunders. Letter to Rosa Waugh Hobhouse, 19th December 1962 (Tate Archive).