Marenka Gabeler’s latest article in her series on art and health featuring Victoria Rance LG

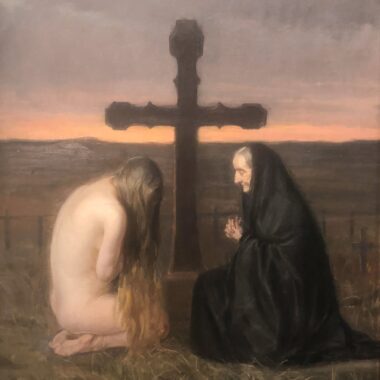

The Art of Hope

Victoria Rance, artist, Green Party parliamentary candidate, and environmental campaigner, opened up a magical world to me. We talked about Bolivian death rituals and an art which functions as anchor in times of adversity.

It’s still 2020 when we speak, November, and like many of us, Victoria feels anxious about a 2nd lockdown. She had COVID 19 very badly at the end of March, as did her daughter, who became seriously ill. Her daughter now has ‘long COVID’ and suffers from chronic pain. Recently, Victoria’s brother in law, a famous Bolivian musician, came over to England, he contracted Coronavirus, he died. This is where our conversation starts and it leads us straight into the Day of the Dead.

Victoria’s first description is of a most beautiful Bolivian family ritual, a commemoration held for her brother in law, on zoom. She describes it as a moment of special connection, despite the physical distances. Relatives, spread across the world but together on screen, show charming altars consisting of photographs, candles, fruit, flowers, and even special bread shapes called Tantawawas or bread babies. The latter are offerings used in ceremonies of encounters with ancestors. Victoria’s sister had made bread llamas and pigs. There were even bread ladders, for the dead to climb to heaven.

The Zoom session was spent talking to the brother-in-law. It’s a bit strange when you start off, Victoria said, addressing someone who’s dead as if they are alive and present, but after a while you get used to it and it becomes very therapeutic. Every family member of all ages joins in, in turn.

The story reminds me of when I searched for a way to bring the dead back to life in Indonesia, some years ago, quite soon after my Indonesian grandmother, from my father’s side, had passed away.

On an artist residency to the island of Sulawesi, my sister and I visited the Tana Toraja Tribe. They make effigies of their deceased, called Tau Tau. Carved out of wood, these dolls are dressed in the actual clothes of the deceased. At first they are kept in the home of relatives, who talk to them as if the person who died is still there. After some time the Tau Tau are moved and placed on balconies along rock facades in the rainforest. They are imbued with the deceased’s spirit through an elaborate ritual involving the sacrifice of various animals. Somehow the Tau Tau make a transition from inanimate to animate. I never got to grips with how the Tau Tau actually came to life, but listening to Victoria it dawned on me that it might have something to do with an intentional mindset to surrender. Wouldn’t surrendering to an idea be the key to open up the mind and the heart to a sense of possibility?

I read about Victoria’s beautiful project, I Wish, on her blog. People would come to her studio to have a private conversation and tell her their deepest wish. From these encounters, Victoria would take inspiration to make little talisman like art works to then give back to the person as a keepsake. ‘Something to remind you of your dream’, she says.

It all started in her studio in Deptford in 2013, but quickly grew into an artist’s residency at the Woolwich Hospital Children’s Ward. The conversations she had with parents and children could actually be seen as a type of counselling, I feel. Victoria became an ear, someone who listens to people’s story.

I see a picture of a dolphin and a fox made out of pewter. They fit into the palm of a hand. A doggy with a fabric pouch to keep him safe, colourfully decorated with buttons and bells. Hands of a child are holding a little felt cushion with the image of a tractor stitched onto it.

All these little objects suggest personal stories. A simplicity and almost childlike honesty emanates from the work. The objects don’t pretend any grandeur, rather, they suggest they’ll be dearly cherished and tucked away in someone’s pocket.

The size contributes to a sense of intimacy, ‘I felt like making small things’, Victoria says, ‘a democratic type of art, something people who can’t afford larger, more expensive works can still own’.

We talk about the role of art in health care. Victoria highly values art’s ability to make human connections. Through talking to people about their wish, she somehow creates a special place of trust. ‘It’s not just about art’, she says. ‘The important thing is the conversation, the space you create. Images come up in that space of energy’, she continues. ‘Art becomes a vehicle into another form of imagining health, different from medicalisation. Improving the health of the psyche helps the body to recover.’

In his book, ‘Art As Therapy’, writer philosopher Alain de Botton discusses art as a tool to offer us assistance in caring for our inner needs. ‘Getting something out of art won’t just mean learning about it. It will also mean investigating our (inner)selves.’ 1 He explains that for long periods in history religions and governments have considered art as a fundamental shaper of personality and public life. That religions and governments wished to direct art according to their particular understanding of the needs of the soul and of society. Where today many people might not be able to make certain spiritual connections through the rituals of religion, De Botton believes there is a gap art can fill.

Victoria’s Art helps us to open up to our vulnerabilities so we might share and find ways of connecting to others. It is these connections that help us in our processes of healing.

As Leonard Cohen once wrote: ‘There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in’.

Victoria’s ‘I wish’ project is an art that reaches out to anyone in need of a sparkle of hope. And I think I can say safely that hope is something we all need these days.

Marenka Gabeler LG, London, February 2021.

1 Botton, Alain de. ‘Art as Therapy’, Phaidon Press, 2013, p 67.

Twenty five images made during the 2017 I Wish residency at Queen Elizabeth Hospital Woolwich are now on permanent display in the corridors leading to the children’s wards.

I want to thank London Group members Julie Held, Bryan Benge, Judith Jones, Victoria Rance, Susan Wilson, Eric Fong and Suzan Swale for letting me interview them to inform this topic. This is an ongoing project. I continue my investigation and aim to include interviews with the other members I spoke to in subsequent articles. See below for further articles.

Art and Health, A Story

Interview 1 Julie Held LG – Death As A Thread Through Life

Interview 2 Bryan Benge LG – The Art Of Caring