“It is important to show people who don’t often get to see the light of day…there’s a competency, pride and dignity there”.

Jon Blackwood discusses the films of Amanda Loomes PLG.

.

I first encountered the films of Amanda Loomes during the exhibition Triple Harvest at Fermynwoods Contemporary Art, in Corby. Amanda was one of six artists and was part of a group exhibition that responded to three separate archive films on the historical steel industry in that town, which closed down in the last part of the twentieth century. Her contribution to that show, Combine (2020), is discussed further below, but the film contains trademark empathy, painterly framing, a sculptor’s interest in and appreciation of materials, and the space for people to become characters rather than subjects in the film’s narrative development. It was this combination of qualities that, in my view, made the film stand out amongst the selection of works.

Through discussion in the subsequent year, it has been possible to get to know the artist and her work better, and to understand not only the delicate and subtle balancing of the films, but also her uncertain and unusual trajectory towards being a full-time artist.

Amanda Loomes grew up in North Yorkshire in the 1970s and 1980s. Her parents were tenant farmers and later owned their own land; the sale of the farm and the emotional divesting of farm stock and chattels in the early 2000s was the subject of her first-ever film as an art school undergraduate. Whilst hers was not an artistic family, nonetheless there are strong memories of a local limestone crag, visible from the house, and a collection of paintings of that same crag on the walls. Perhaps this was an early exemplar of the relationship between an object and image, although creative endeavours in the house tended to be focused on craft, and on making for practical ends.

At that time, Amanda was interested in art but there was no particular route or outlet. On leaving school in the middle 1980s she found herself working her way towards a civil engineering career with Wimpey Construction, in the broader context of women being encouraged into male-dominated science and engineering careers. For the next decade, she worked extensively around London and the South East on commercial construction projects such as the building of supermarkets and offices. The relationship between her civil engineering career, and subsequent art practice, is complex. Civil engineering does recur as a theme, as in the films Multi-story and Spare (2014), which focus on a building at 80 Bishopsgate in London. This was a site Amanda had helped construct, in the 1990s, before returning to record its demolition in her new capacity as a filmmaker, fifteen years on.

Amanda’s career in civil engineering lasted for just over a decade, and it was during that period that the desire to pursue an interest in art began to make itself felt. Attending clay sculpting night classes during the building of a supermarket in Southend, she gradually worked towards an A-Level in art and then a foundation course at Reigate School of Art. The change of gear was, however, difficult to explain to wider family and friends who saw her passing up a secure job and career for the precarious uncertainties of life as an artist. It’s a topic that is still little visited. “People can feel quite threatened by art…they can struggle to get it, and are made to feel slightly inadequate. I think there’s a lot of complexity around that,” she observed subsequently.

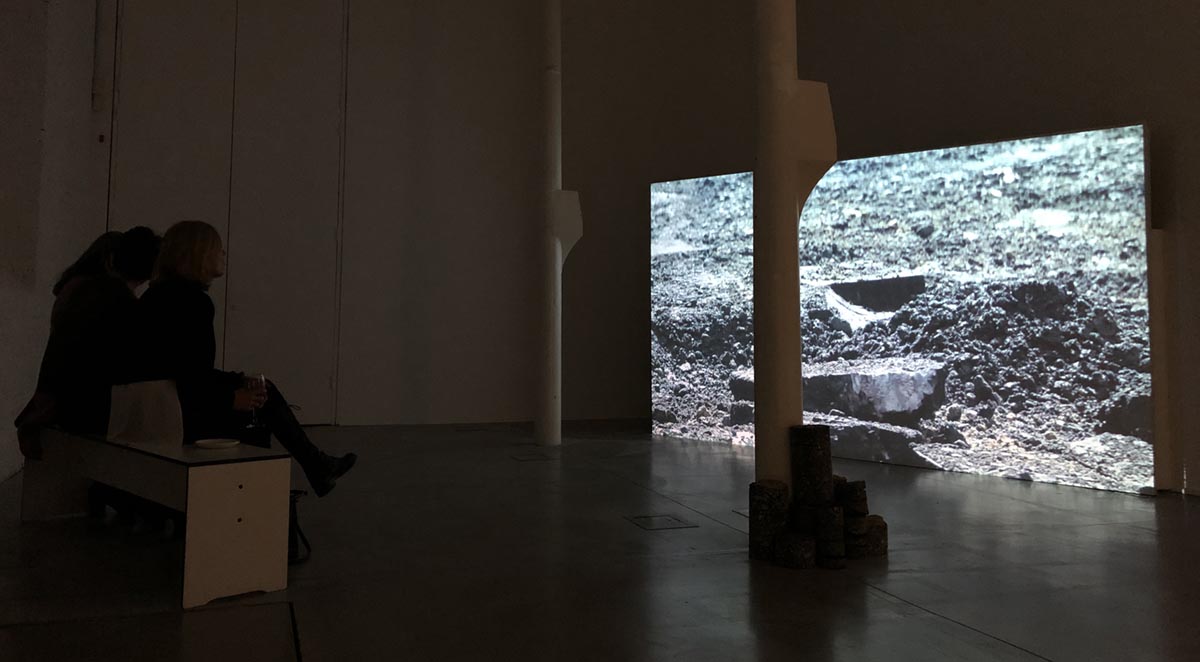

Amanda’s interest in film developed in the context of the painting department at Chelsea College of Art from 2000 to 2004 followed immediately by a Master’s at the Royal College of Art. It is fascinating to observe the fine balance in the mature practice between this painterly training, and a long-frustrated sculptor’s interest in materiality and the use of materials in specific settings. The films contain very specific painterly elements- framing and a meticulous attention to detail in respect of colour and light- yet at the same time, display a basic fascination with the quality of different materials, notably asphalt, concrete, and wood; the making and re-making of landscapes through extractive practices such as forestry and quarrying. Beyond these material concerns, some of the films have subsequently been displayed as part of sculptural installations, rather than simply as moving images.

.If Amanda’s films can be read as a meeting point between a painterly training and unrealised sculptural ambitions, the common language of such an encounter is time. By this I mean time not as duration, but rather time spent and invested in realising a film as a project, and the insistence that even with attention spans shortening, ever more pressed and impatient audiences are encouraged to invest time in appreciating the qualities of the work and follow the characters that she introduces us to.

This last is an important point. The working-class characters in these films are never shown- their voices are disembodied, like in a radio programme. It’s a very subtle way of luring-in an audience. In 2021 we are so used to looking at talking heads on a screen that we pay attention neither to their appearance nor especially to what they are saying. Muted talking heads are often a backdrop in office lobbies or the non-places of airports or shopping malls, barely noticed details in a visually saturated environment.

In Amanda’s films, we have to listen to what the voices are saying and try to build our own relationship between their words and what we see in front of us. The result is a composite portrait where we never actually see the sitter, but leave the film at the end understanding them. This is a counter-intuitive strategy in a culture where surface appearance has never mattered more, and where emojis are battling for dominance over the written word.

These artworks offer rare dialogues between the language of fine art films and the languages of extractive industry; construction, demolition, forest management, material science. The artist speaks of the uncertainties of the early stages of each film, whereby the preconceptions that her characters may have about contemporary art, and film making, are broken down slowly through familiarisation. At the same time, any ideas or personal notions of what her characters do in their day-to-day job are also broken apart.

I use the word character rather than subject quite deliberately here. There is a sense over the course of these films that the disembodied voices grow into full characters who we can empathise with, and understand, even if their line of work is something we have never before considered- almost going through the same process as the artist herself in making the film. There is no uneasiness or falsity in the relationship between this filmmaker and her characters; we are left with the sense of an equal relationship and perhaps even trust, grown over time.

Amanda’s works are based on close, participatory observation in her characters’ lives. Part of this observation is an appreciation of skill; of watching people complete a task that they are very good at, over a period of time, a pleasure deriving from her days in the construction industry. In her treatment of the people who appear in her works, I also have the sense of a muscle memory from working on building sites; the short-term, precarious, but intense nature of working relationships in that environment. It is possible to work with people on a site for three to six months, and then never to see them again; the sudden fracturing of a professional closeness from the previous Friday, on a new job the following Monday. In the types of people that Amanda portrays and works with in her films, there is something of that old lost rhythm from her days as a civil engineer.

Speaking on her working practice, Amanda observes that:

“I bring a project mentality to my work…in construction you’re paid to observe a set of rules. You have to really care… it’s a really tough place to work…I think there’s an element of having to dig in and be bothered that applies to both art and construction.”

Part of the “digging in” comes in building a coherent narrative. This can take repeated filming and careful editing to shape over months on site and in the studio. It’s another interesting crossover with the practices of painting and sculpture; adding-in layers and cutting away unnecessary material. Critical in building the narrative, is the artist’s foregrounding of the characters that drive the narrative, whilst she remains in the background, in control of what we see and hear but little observed as a presence in the films. Having looked across a range of work from more than a decade, Amanda’s presence through absence in the finished pieces is a unifying compositional trait.

One other recurring feature is giving people space to express themselves. This is tremendously important to the artist. In one of our earliest conversations we discussed Gustave Courbet’s The Stone Breakers (1849, destroyed February 1945). In a similar way to Amanda’s films, both the characters in this lost realist painting turn their faces from us, but we are invited to empathise with the backbreaking, difficult and relentless nature of their work. Part of the currency of French realism in the mid nineteenth century was the depiction on a large scale of working-class characters, something that had never been done consistently before in the history of painting, other than incidentally.

The artist stated: “It is important to show people who don’t often get to see the light of day…there’s a competency, pride and dignity there”. Perhaps obliquely, as Amanda’s own thinking around class identity is still in process and subject to many contradictory currents, the body of work as a whole, stands as a composite portrait of the English working classes in the early twenty first century. This is at the tail end of a period in politics where working-class power and self-expression has been systematically dismantled through de-regulation of working practices, the eclipse of trade union influence, and a fundamental shift away from notions of community towards notions of the individual. Indeed, this loss of community is another recurring theme in the work.

Whilst the artist does not claim to be a “working class artist”, the fundamental structural changes impacting on the working class, and how those changes play out on an individual level, are important themes. Examples from recent art history of collectives or individuals dealing with class issues are also important exemplars of practice; for example, the Amber Film & Photography Collective in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, or the Artist Placement Group, founded in the late 1960s by John Latham and Barbara Steveni, and which negotiated placements for artists in industry to the mid-1970s. One such placement, that of sculptor Garth Evans with the British Steel Corporation between 1968-71, was frequently referred to in the conversations that underpin this essay.

However, there is a critical difference between the strategies adopted by APG. The public-school educated Latham and Steveni thought nothing of approaching leading figures in British industry at that time, to arrange a placement for a contemporary artist; in our time Amanda, by contrast, tends to enter a working environment a little more “under the radar” and to try and understand its visual and narrative possibilities through the eyes of the ordinary workforce.

If the aim of the APG was (in part) to explore the possibilities of the artist-as-worker, and to demystify the practice of contemporary art by practical example in the workplace. Amanda’s films carefully make common cause between the artist and a working class both relegated to the status of expendable units; permanently insecure members of the precariat shifting from one paid job to the next with little continuity of community. It’s a trajectory carefully observed by Gregory Sholette in his 2016 book Delirium and Resistance.

Having outlined some of the formal and contextual issues which recur in these artworks, in the last part of this essay I’d like to look closely at three representative samples of the work, in order to draw out our understanding of them further.

In 2014 the artist returned to a building she had worked on as a civil engineer, this time as a filmmaker. This was in Bishopsgate in London, devastated by an IRA bomb on 24 April 1993., The artist was one of the civil engineers that helped to re-build and restore the damaged buildings after an insurance pay out. The building re-opened in 1998 only to be demolished to make way for the 100 Bishopsgate development that opened in 2015. This is one of the few films that makes a direct link between the very different parts of Amanda’s working life.

The short films resulting from this project, Multi-story and Spare (both 2014), reflect on the shaping and moulding of the doomed building by the forces of capital. To the layman not involved in sales of land and property, the expensive reconstruction of a damaged building, only for it to be demolished thirteen years later for another project as central London land and retail /leisure/living space became ever more at a premium, seems somehow wasteful and immoral. Yet these films are stories not so much of a change in building but a change in the City itself, the logical outworking of 1980s deregulation, and the emergence of London as a global financial hub where property and land use can change several times in a human lifetime according to volatile market trends. It is a snapshot of the over-writing of the old London- a former imperial capital site of industry and manual labour, a site of conflict for much of the twentieth century, into a global megalopolis in a state of permanent flux, that even residents struggle to keep up with.

Laid against these meta-problematics are sensitively recorded micro-observations; the recording of doomed fragments of relatively new material, awaiting destruction; of empty former office spaces on the point of obliteration; the thoughtful observations of an unseen demolition contractor, who talks through the process of the work and how it is perceived by others. Stereotypes of demolition workers as thoughtlessly swinging a wrecking ball and levelling everything in their field of vision are challenged.

In point of fact, we are introduced to the notion not of “demolition” but, literally, “de-construction”; the methodical reversal of all the construction steps taken by Amanda and her colleagues, as civil engineers, in the 1990s. The artist subsequently joked, ”Almost everything I built back then has subsequently been demolished”. Humour aside, these films leave a sense of loss, of waste, and the melding of those two into a more sublime incomprehension at the operation of capital.

If there is an understated personal involvement in these Bishopsgate films, there is no such quality to the two more recent films we’ll discuss; Surfacing of 2019, and Combine finished in the following year.

Surfacing is a touching portrayal of a gang of road workers, following them as they re-surface various roads in inner London. There are two significant developments notable in the five years that passed between this work and Multi-story; the framing is much more refined, even aestheticized in places; we also have a much greater insight into the mindset of the group of men, both as a collective and as individuals.

We have a real sense through this film of the artist slowly making the individuals comfortable with the creative process, and encouraging them to become increasingly self-reflective through dialogue. At the beginning of the film, the men are in places awkward and laughingly self-conscious, but by the end they are openly reflecting in their life choices, their routes into the work, the camaraderie of the group and the privations of the job- laying hot tar in the dry heat of London in high summer. The way in which Amanda draws these stories out of the men as the film develops is really noteworthy.

Resurfacing gangs know they are rarely popular with the public; blocking the way of impatient drivers, and creating dirt, mess and sickly smells for passers-by. One of the starkest framings of the film is of the men and their machinery re-surfacing a road in the heart of commercial London, with the branded flags of high-end jewellery and fashion concerns flapping from buildings at either side of the road.

One of the men reflects; “Some of the people round here…it’s millionaires…they probably look at us like we’re scum…always dirty, head to toe black…but they’re the ones that always moan if there’s potholes, y’know…we’re no different, are we, we just do different jobs.” It’s a poignant remark at that moment in the work, inviting reflection on the basic invisibility of essential workers- until the work that they do fails and needs replacing.

There’s also a meditative quality to this work, encouraged by the repetitive, pressured and skilled work patterns captured in the film, and the tight use of the colour palette; the black-greys of the setting tarmac against the fluorescent yellows and oranges of plumb lines and worker’s jackets. It’s possible simply to half close the eyes and enjoy the blurred colour and the sound track, a meditative chant arranged by Dilpreet Bhatia. It is somehow reminiscent of the music of one of the earliest art-films on extractivism and the world slowly moving out of balance- Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982). The work of making, re-making, layering, over laying, smoothing down final crumbs of tarmac with hand tools and roller also inviting comparison with painting and the contribution of the unconscious mind to making artwork through learned and repetitive movements.

The final film and the most recent exhibited project, Combine (2020), brings together the visual and ruminative qualities of Surfacing with the concern for material use and transformation from the earlier films. As part of Amanda’s response to the selected archive films relating to Corby’s steel heritage, Combine bases itself at Ketton Cement Works, fifteen miles north-east of Corby. Many of the artist’s preoccupations are brought together effectively in this film, alongside the edited, visually rich clips from the heyday of British Steel in Northamptonshire.

The strong sense derived from the archive film is how the community grew up around the steel works in Corby, not only amongst the workforce but also in the way the rhythms of steel making provided a baseline to the town’s wider activities. There is a sense of pride in the work completed, at the levels of skill displayed in all aspects of steel making from extracting iron ore to production processes; a sharing of the credit for a common endeavour. A greater understanding of how all the individual roles in production fitted together.

Whilst the steelworkers of Corby from two generations ago may have felt at home in the contemporary cement works, with its noise, dirt, heat, and heavy plant, they would have been perplexed by the chimerical “order” brought to the process by a variety of computerised manufacturing systems, visible through a series of screens controlled by a highly skilled technician.

This process of “chasing the chemistry”, ensures a computer-controlled perfection in the manufacture of cement. Occupations that are just as skilled, and crucial to the process, are the blasting of new raw material from the landscape, and a linked land management programme that aims to create the conditions for post-extractive regeneration. These activities are a parallel to those skilled occupations shown in the archive films from the steelworks, but they are done behind a fence, hidden from public view. They also take place in a much-altered social landscape where the public seems little interested in the skills associated with such work.

The process of cement making, seen on a screen, is very alluring to watch. Perhaps the steelworkers of old would also have found the palpable isolation and loneliness of the film’s subjects upsetting. The values that bound together a past industrial society have gone, even if wonder at the chemistry of the process and respect for long years of service remain. There’s an almost shy, self-effacing series of insights from the workforce, anonymised by the artist; theirs are processes and skills that wider society no longer seems terribly interested in looking at, let alone taking any pride in. This film, similar to Surfacing, is surprisingly intimate and revealing of a sweeping change in our values that has altered us profoundly, yet almost imperceptibly.

Amanda Loomes’ films rest on three solid foundations; a natural interest in and empathy with others, particularly those who, like the artist herself, “fly under the radar” in their work, content to keep displaying and developing crafts and skills developed over a long period of time; a painterly interest in framing, layering, and colour that becomes more refined over time and, finally, a strong interest in materiality. These factors combine together to offer subtle and nuanced portraits of working people, demystifying their work and providing an opportunity to understand overlooked, ordinary lives. These portraits offer a hidden continuum between Amanda’s early working life as a civil engineer, and her current artistic practice. It seems clear that, even if many of the buildings that she worked on have already made way for others, her films will acquire much richer patina of interest and interpretation with the passage of time.

Jon Blackwood