Marenka Gabeler’s latest article in her series on art and health featuring Bryan Benge LG

It’s early November, this moment in time is a tough one. We have just entered a second lock-down in England. Corona Virus numbers are spiking, we have not had a Corona vaccine breakthrough. The American election hasn’t happened yet. Brexit is still looming.

It’s a cold and rainy morning in Norfolk. I light up the wood burner. There is something so comforting about an open fire.

Interview:

Bryan Benge: The Art Of Caring

‘I’m struggling at the moment, with the isolation’, Bryan says. London Group member Bryan Benge is on the other side of the line. We haven’t met before but we are both glad to speak.

Bryan can feel the psychological effects of a year with Corona Virus. He tells me he goes walking for miles and miles most days, around where he lives in Epsom or his place in Devon.

He lives with his wife, but his brother lives in north London with his family, and Bryan hasn’t seen him for a long time. He also has a nephew who works in a hospital, and he fears he might not be able to see him for another year. Bryan misses contact and conversation. This lack of contact is affecting him.

Apart from being a London Group member, Bryan belongs to a small group called Collect Connect. The founding members, Dean Reddick and Alban Low, and Bryan him self, organize exhibitions for ‘The Art Of Caring’, an initiative in support of the NHS. Collect Connect sends out open calls to artists, asking them to respond to themes related to health care.

‘The Art of Caring, what a great name!’, I think to myself.

Bryan really wants to connect with people who have no or little experience of expressing themselves through art. The people he manages to get involved he calls ’cab artists’.

In the last three years, Alban Low has worked closely with the School of Nursing in Surrey to enable student nurses to exhibit work alongside artists.

The head of nursing encourages creativity. ‘She is convinced that engaging in art making will make better and more responsible nurses’, Bryan says. And although the nurses felt intimidated to start off, Collect Connect came up with ways to lower the threshold by asking them to write something about themselves. The nurses soon got engaged and in no time were stitching their names in thread. The rest of the works just flowed from there. ‘They got such a buzz out of being taken seriously’.

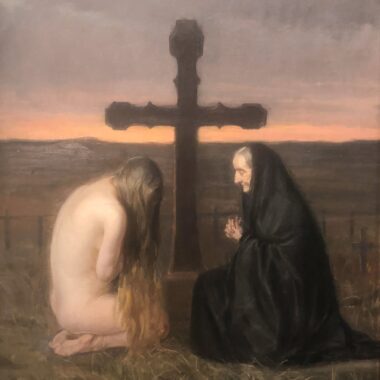

I ask Bryan about his own art practice. ‘My work mainly deals with issues of memory. As a child I spent a long time in hospitals, so some of my work has dealt with this in a visual way’.

Bryan tells me how he suffered from asthma and eczema as a young child. Between the ages of 4 and 5, he was hospitalized for long periods after reacting badly to a smallpox vaccine. He remembers wandering the corridors in the hospital, looking for his parents, thinking he’d been abandoned.

Earlier, at age 3, he suffered from double pneumonia and a double collapsed lung. One of Bryan’s first memories is of lying in the arms of his father, his aunties gathered around, and him wondering why they were all looking at him.

‘It was a first moment of coming into consciousness’, he says.

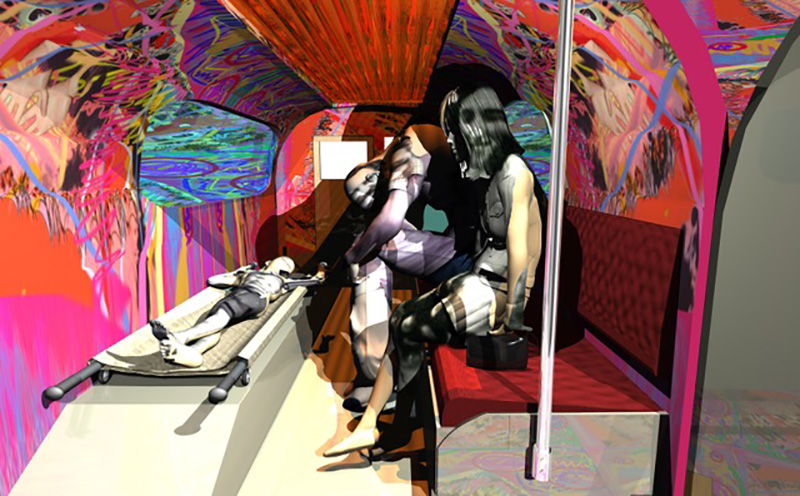

‘Matchbox’ refers to that time in his life. I look at a digitally manipulated image of a room with a boy sitting on a hospital bed. Old black and white photo images, integrated in the virtual space, show nurses in hospital wards. Walls and floors are merged layers of brightly coloured shapes and patterns. The bold boy is playing with match boxes, his is back turned towards us, the face of a man projected onto his body. It is Bryan as a child. His father had given him the boxes. I find the mood a bit cold and claustrophobic, fitting the idea that the boy might feel abandoned in this strange place, retreating into an imaginary world of play.

We observe the space from an areal point of view. It gives the viewer a slight distance from what’s happening. Almost akin to time itself in creating a certain distance from the childhood experience.

Bryan, originally a painter, finds more flexibility in making digital work nowadays. ‘There are many ways to arrive somewhere. The accidents (that you might like to see happen in the creative process of painting), still happen’.

‘Memory builds us how we are. Informs on the way we are’. Bryan feels that making work about memory makes him able to deal with the past, internalizing it. To make sense of memories he uses a mix of cognitive skills he’s learnt and turns them into an artistic language.

He quotes Walter Benjamin, ‘Memory is not an instrument for surveying the past but it’s theatre.’ Walter Benjamin, Berlin Childhood (1900)

‘It’s the act of playing out those triggers that make us respond to the world in certain ways’, he continues. ‘Cave people drew a buffalo or horse, maybe to have a certain control? Maybe it’s a survival thing’.

We return to the Art of Caring. ‘This year we were going to install the works in the small gallery of St Georges Hospital but unfortunately this has now been cancelled due to the Coronavirus’. Connect Collect are not sure when they can return to the Art of Caring. Everything seems up in the air.

I want to thank London Group members Julie Held, Bryan Benge, Judith Jones, Victoria Rance, Susan Wilson, Eric Fong and Suzan Swale for letting me interview them to inform this topic. This is an ongoing project. I continue my investigation and aim to include interviews with the other members I spoke to in subsequent articles. See below for further articles.

Art and Health, A Story

Interview 1 Julie Held LG – Death As A Thread Through Life

Interview 3 Victoria Rance LG – The Art Of Hope